Peripheral Training for Athletes and When To Implement It

Posted by Matt Russ on 5th Feb 2016

By Coach Matt Russ for USA Triathlon Multisport Zone

Athletes commonly question whether participation in one sport or activity will enhance performance in another. As with most training related questions it is really a “depends” answer. However, it is important to recognize that the first rule of training is specificity. You do not become a better runner by cycling, or a better swimmer by skiing. This applies to strength training or “cross training” as well. Each type of activity may enhance or detract from your overall goal of selected endurance sport performance depending on how much volume, how frequently, and at what point in the season it is incorporated. I call training that is not directly sport specific “peripheral training.” How you organize and integrate your peripheral training may be critical to the success of your season.

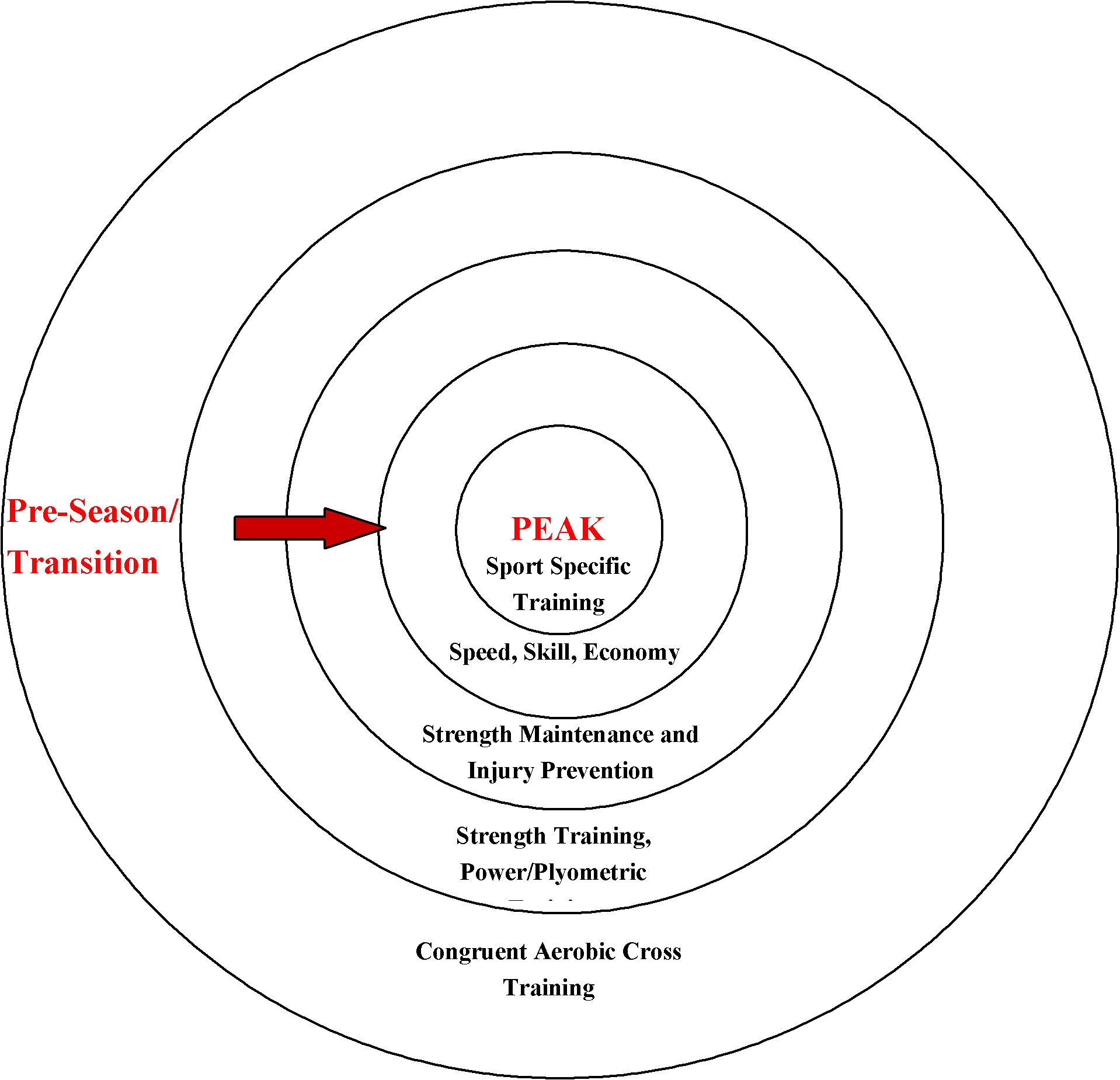

As you approach your peak or goal race your training should become progressively more specific and race like. There is often little room in a time crunched triathlete’s schedule for much beyond highly specific training. Where does strength training, economy and skill, injury prevention, as well as cross training fit in? If you view your season as a series of concentric rings, like the ripples a pebble makes when dropped in a pond, visualize the most outer ring as the pre-season or transition phase. The center would be your most specific or "peak" training. The outermost ring is the farthest point in the season from your goal race and would generally occur directly after your last peak. This is a typical model of how you might incorporate various types of peripheral training appropriately during your season. The closer you are to the center peak less emphasis should be placed on peripheral training.

Congruent Aerobic Cross Training. After accomplishing a peak race, athletes not only require a physical rest but a mental break as well. I like them to put down their sport specific training for a while if possible, but I don’t want a complete shutdown that will require extensive rebuilding of fitness. I encourage them to take up other aerobic activities that will maintain fitness. For a triathlete this may mean mountain biking, cross country skiing, hiking, rowing, or anything that essentially keeps them moving. I am not a fan of incorporating ball sports or activities that require fast lateral movements. Their bodies are highly conditioned for triathlon at this point in the season, and it leaves them susceptible to injury if a rapid shift in sport takes place. For this reason I encourage them to enjoy congruent aerobic activity (not training) that is unstructured and fun.

Strength Training/Plyometric Training and sport specific training can be like oil and water. Not only can plyometrics degrade the performance of a key running speed work out, it can rapidly injure the unprepared. On the flip side it might be just what the athlete needs to fast forward their progress, restore balance, and shore up the weak points in the kinetic chain. The key is timing and progression. After a strength acclimation period this type of training can be incorporate 3x per week or more as long as the sport specific volume (swim/bike/run) is low and intensity is low. Typically this would be in an athlete’s base phase. Emphasis should be two part- restoring muscle balance and strength/power, and choosing exercises and movements that will enhance sport specific performance. Take the two Latissimus exercises below for example: the one arm row and the other using a Vasa Trainer. Both work the “Lats” which are essential for swimming strength and power, but the Vasa Trainer utilizes a movement pattern very similar to swimming. It targets the muscles in a sport specific manner. It is important to choose exercises that mimic the balance and movement patterns required for triathlon. Athletes may gravitate towards the leg extension machine or overhead presses, but both of these movements have very little application to triathlon. The length of a strength or plyometric phase will vary with each athlete but the most important thing to note is that as sport specific volume comes up this peripheral training must be tapered.

Strength Maintenance/Injury Prevention. The incidence of injury in ultra-distance triathlon has been estimated as high as 90%. These are horrible odds. The sport of triathlon requires repetitive motions in a restricted range of motion. This often leads to overuse injuries and/or muscle imbalances. It is important to note that when injury does occur it becomes the athlete’s weak link that has a high likelihood of failure in the future. For example, after a tendon injury heals, the collagen that forms is not the same type as a healthy tendon, it is more susceptible to injury. Athletes accumulate these injuries over the years. Muscles shorten and others are stretched to the point that proper joint function and/or impingement can occur.

Great gains may be made in strength and stability through an appropriate phase. The conundrum is maintaining what you have built once sport specific training is increased. The good news is that it takes very little volume to maintain strength and neuromuscular firing in a particular area. Often a consistent routine of as little as 20-30 minutes, 2-3x per week, is enough volume to ward off injury in areas susceptible to break down. It may be hard to find this extra bit of time in an already time crunched training and lifestyle, but a targeted and specific routine may be what gets you to the start line. IT Band Syndrome, shoulder impingement (swimmers shoulder), Patella Femoral Syndrome, and Achilles tendonitis are common injuries among ultra-distance athletes and require a specific set of maintenance exercises to keep them from re-occurring. These must be conducted and balanced appropriately nearly year round to combat the enormous amount of stress, strain, and break down they body is put under. Greater emphasis should be placed upon strength maintenance and preventative training for older athletes or those with a history of over-use injury.

Speed/Skill/Economy. Athletes often suffer under the notion that simply training hard and/or often will lead to a linear progression in speed. The truth is that unless economy and efficiency are addressed, progress will plateau. Speed/skill training is often overlooked as it requires expertise the athlete may not possess, time, and often additional money for expert instruction. But the more experience an athlete gains in a sport, the closer they may move towards the glass ceiling of their physiological limiters. A break-through in economy may lead to the PR they have been seeking. This is particularly applicable to the swim and run, however running economy is least likely to be addressed. We receive no formal instruction in proper running form from our early childhood as we do in other sports- it is assumed to be natural. But the truth is that great runners run very differently than most runners. Almost invariably, great runners received years of instruction under a quality coach that included regular drills, speed work, and evaluation.

If you are at a plateau or would like to fast forward your progress, incorporating regular speed/skill training may be just what is required. It is best to integrate instruction prior to a peaking phase. Overall intensity should be relatively low and there must be enough room for the additional volume. That being said, a little amount of speed/skill training incorporated regularly is more effective than a workout dedicated solely to it. Working on just 1-2 aspects of more economical form during each workout will offer greater reinforcement. It is best, however, not to alter form in a final peaking phase. It takes time and patience to re-work inefficiencies and there may even be an initial drop in economy. Greater stress is placed upon different muscles groups and they must acclimate to the new loads placed upon them. It is also difficult to work on economy during high intensity sessions that require great mental focus on performance metrics. For these reasons I don’t attempt to drastically alter mechanics prior to a race.

Sport Specific Training is almost a season long constant in some form. Volume and the fitness substrates that are targeted may change but for a triathlete they are swimming, biking, and running for over 90% of the season. One mistake athletes make is attempting creative ways to boost fitness using different types of peripheral training during a peaking phase. The body is now highly tuned for the demands of race day and even incorporating a new class, although beneficial at one point in the season, may actually degrade athletic performance. Once you are in the linear progression of the final series of stress/recovery cycles leading to your taper, focus on the demands of race day + injury prevention. Do not incorporate any new stress as the body will likely not react well to it, and there is virtually no room for peripheral training in a proper peaking phase. The more specific your training is to the demands of race day- course, intensity, environment, equipment, etc., the better prepared you will be for you race.

There are a great number of moving parts to a given season. Training should constantly be changing, evolving, and progressing towards the ultimate goal. The great thing about structuring your peripheral training properly is that it has the added benefit of reducing boredom and de-motivation. You can only be kept in peak shape for a small window of time, and this applies to your mental frame as well. Don’t underestimate the motivational and social impact different types of training may have on your season. Great athletes are seldom formed in a social vacuum. At key points in their season they are training highly specifically to their race goals, but at other points they are enjoying the social interaction and humor that often occurs in classes, groups, and cross training activities.

Matt Russ has coached and trained athletes up to the professional level, domestically and internationally, for over 20 years. He has achieved the highest level of licensing by both USA Triathlon and USA Cycling, and is a licensed USA Track and Field Coach. Matt is Head Coach and owner of The Sport Factory, and coaches athletes of all levels full time. He is also free- lance author and his articles are regularly featured in a variety of magazines and websites. Visit https://sportfactoryproshop.com/ more information or email him at coachmatt@sportfactory.com